No products in the cart.

Chandas

Sanskrit prosody or Chandas refers to one of the six Vedangas, or divisions of Vedic studies. It is a study of poetic meters and verses in Sanskrit. This field of study was central to the composition of the Vedas, the biblical canons of Hinduism, so central that some later Hindu and Buddhist texts refer to the Vedas as the Chandas.

Chandas, as developed by the Vedic schools, were organized around seven main meters and each had its own rhythm, movements and aesthetics. Sanskrit meters include those based on a fixed number of syllables per verse and those based on a fixed number of moras per verse.

Extant ancient manuals on Chandas include Pingala’s Chandah Sutra, while an example of a medieval Sanskrit prosodic manual is Kedar Bhatta’s Vrittaratnakara. The most exhaustive compilations of Sanskrit prosody describe over 600 meters. This is a considerably more extensive repertoire than in any other metrical tradition.

The term chandas (Sanskrit: चैदः/चैदस् chandaḥ/chandas (singular), चैदाआसि all-based, pleasing, chandāṃ, all-based, pleasing, graceful, chandāṃsi to look good, feel pleasant and/or something that nourishes, pleases or celebrates”. The term also refers to “any metrical portions of the Vedas or other compositions”.

History

The liturgical hymns of the Rigveda include names of metres, indicating that the discipline of Chandas (Sanskrit prosody) appeared in the 2nd millennium BC. The Brahmanical layer of Vedic literature, composed between 900 and 700 BCE, contains the complete expression of Chand. Panini’s treatise on Sanskrit grammar distinguishes Chandas, as the verses that make up the Vedas, from Bhāṣā (Sanskrit: भाषा), the language spoken by people for everyday communication.

Vedic Sanskrit texts use fifteen metres, of which seven are common and three are the most common (8-, 11- and 12-syllable lines). Post-Vedic texts, such as the epics and other classical Hindu literature, use both linear and non-linear meters, many based on syllables and others based on carefully crafted verses based on repeating moré (matras) counts. per track). About 150 treatises on Sanskrit prosody are known from the classical era, in which about 850 meters were defined and studied by ancient and medieval Hindu scholars.

The ancient Chandahsutra Pingala, also called the Pingala Sutras, is the oldest Sanskrit prosodic text to survive into modern times, dating to between 600 and 200 BCE. Like all sutras, the Pingala text is distilled information in the form of aphorisms that have been widely commented upon through the Hindu bhasya tradition. Of the various commentaries, three 6th-century texts are widely studied – Jayadevacchandas, Janashrayi-Chhandovichiti and Ratnamanjusha, a 10th-century commentary by the Karnataka prosody scholar Halayudha, who is also the author of the grammatical Shastrakavya and the Kavirahasya (literally, Secret of the Poet). Other important historical commentaries include the 11th-century Yadavaprakasha and the 12th-century Bhaskaracharya, as well as Jayakriti’s Chandonushasana and Gangadasa’s Chandomanjari.

Elements

Nomenclature

A syllable (akshara, अक्षार), in Sanskrit prosody, is a vowel following one or more consonants or a vowel without any. A short syllable is a syllable ending in one of the short (hrasva) vowels, which are a (अ), i (इ), u (उ), ṛ (ऋ) and ḷ (ऌ). A long syllable is defined as a syllable with one of the long (dirgha) vowels which are ā (आ), ī (ई), ū (च), ṝ (ॠ), e (ई), ai (ऐ), o (ऌ ) and au (உு), or one with a short vowel followed by two consonants.

A sloka (śloka) is defined in Sanskrit prosody as a group of four quarters (pādas). Indian prosodic studies distinguish two types of stanzas. Vritta stanzas are those that have a precise number of syllables, while jati stanzas are those that are based on syllabic durations (morae, matra) and may contain varying numbers of syllables.

Vritta stanzas have three forms: Samavritta, where the four quarters are of a similar pattern, Ardhasamavritta, where the alternate verses have a similar syllabic structure, and Vishamavritta, where all four quarters are different. A regular Vritta is defined as one where the total number of syllables in each line is less than or equal to 26 syllables, while irregular ones contain more. When the meter is based on moré (matra), the short syllable counts as one mora and the long syllable counts as two moras.

Classification

The meters found in classical Sanskrit poetry are sometimes alternatively classified into three types.

- Syllable verse (akṣaravṛtta or aksharavritta): meters depend on the number of syllables in the verse with relative freedom in the distribution of light and heavy syllables. This style is derived from older Vedic forms and is found in the great epics Mahabharata and Ramayana.

- Syllabo-quantitative verse (varṇavṛtta or varnavritta): meters depend on the number of syllables, but light patterns are fixed.

- Quantitative verse (mātrāvṛtta or matravritta): meters depend on duration, where each line of verse has a fixed number of morae, usually grouped in sets of four.

Light and heavy syllables

Most Sanskrit poetry is composed in four-line verse. Each quatrain is called a pāda (literally “foot”). Meters of equal length are characterized by the laghu (“light”) and guru (“heavy”) syllable pattern in the pāda. The rules distinguishing laghu and guru syllables are the same as those for unmetrical prose and are specified in Vedic Shiksha texts that study the principles and structure of sound, such as the Pratishakhyas. Some of the important rules are:

- A syllable is laghu only if its vowel is hrasva (“short”) and followed by at most one consonant before another vowel is encountered.

- A syllable with anusvara (‘ṃ’) or visarga (‘ḥ’) is always guru.

- All other syllables are guru, either because the vowel is dīrgha (“long”) or because the hrasva vowel is followed by a consonant cluster.

- Hrasva vowels are short monophthongs: ‘a’, ‘i’, ‘u’, ‘ṛ’ and ‘ḷ’

- All other vowels are dirgha: ‘ā’, ‘ī’, ‘ū’, ‘ṝ’, ‘e’, ’ai’, ‘o’ and ‘au’. (Note that morphologically the last four vowels are actually diphthongs ‘ai’, ‘āi’, ‘au’ and ‘āu’, as clarified by the sandhi rules in Sanskrit.)

- Gangadasa Pandita states that the last syllable in each pāda can be considered guru, but guru at the end of a pāda is never counted as laghu.

For mātrā (morae) measurement, laghu syllables are counted as one unit and guru syllables as two units.

Gaṇa

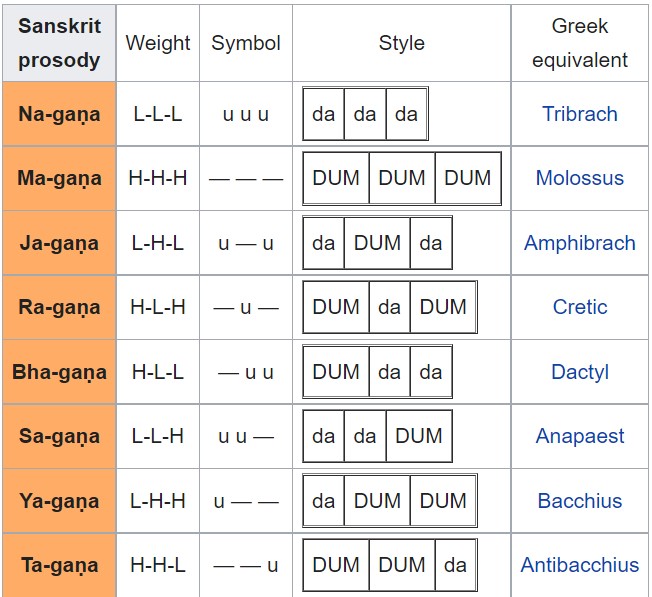

Gaṇa (Sanskrit, “group”) is the technical term for the pattern of light and heavy syllables in a sequence of three. It is used in treatises on Sanskrit prosody to describe metres, according to a method first propounded in Pingala’s chandahsutra. Pingala organizes the metres using two units:

- l: a “light” syllable (L), called laghu

- g: a “heavy” syllable (H), called guru

Pingala’s method described any metre as a sequence of gaṇas, or triplets of syllables (trisyllabic feet), plus the excess, if any, as single units. There being eight possible patterns of light and heavy syllables in a sequence of three, Pingala associated a letter, allowing the metre to be described compactly as an acronym. Each of these has its Greek prosody equivalent as listed below.

The seven birds: major Sanskrit metres

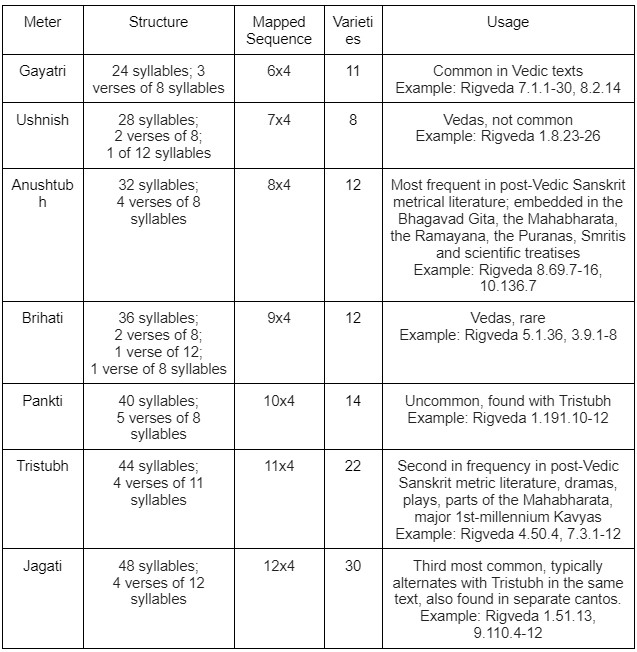

Vedic Sanskrit prosody included both linear and non-linear systems. Chandas field was organized around seven main meters, state Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus, called “seven birds” or “seven mouths of Brihaspati”, and each had its own rhythm, movements and aesthetics. The system mapped the non-linear structure (aperiodicity) into a four-verse polymorphic linear sequence.

The seven main ancient Sanskrit meters are three 8-syllable Gāyatrī, four 8-syllable Anustubh, four 11-syllable Tristubh, four 12-syllable Jagati and mixed pāda meters named Ushnih, Brihati and Pankti.

In India, the Chandas are considered one of the five categories of literary knowledge in Hindu traditions. The other four, according to Sheldon Pollock, are Gunas or expression forms, Riti, Marga or the ways or styles of writing, Alankara or tropology, and Rasa, Bhava or aesthetic moods and feelings.

The Chandas are revered in Hindu texts for their perfection and resonance, with the Gayatri metre treated as the most refined and sacred, and one that continues to be part of modern Hindu culture as part of Yoga and hymns of meditation at sunrise.