Shiva, also known as Mahadeva, is one of Hinduism’s most important deities. In Shaivism, one of Hinduism’s primary traditions, he is the Supreme Being.

The Sanskrit word “iva” (शिव, often transliterated as shiva) denotes “auspicious, propitious, cordial, benign, kind, benevolent, friendly,” according to Monier Monier-Williams. In folk etymology, the root words for iva are śī, which means “in whom all things lay, pervasiveness,” and va, which means “embodiment of grace.”

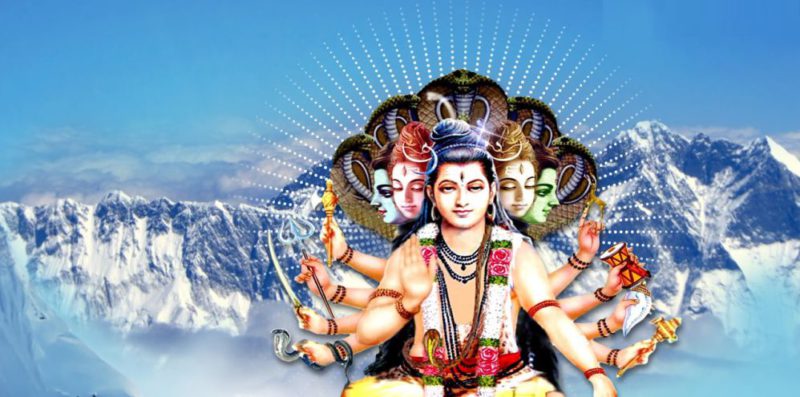

Within the Trimurti, which also includes Brahma and Vishnu, Shiva is regarded as “The Destroyer.” Shiva is the Supreme Lord of the Shaivite religion, who protects, changes and creates changes the cosmos. Devi or the Goddess, is considered as one of the highest in the Shakta religion, although Shiva is adored with Vishnu and Brahma. A goddess is said to represent each person’s energy and creative power (Shakti), with Shiva’s equal complimentary companion, Parvati (Sati). He is one of the five comparable deities in the Smarta tradition’s Panchayatana puja.

Shiva is the universe’s primaeval Atman (Self). Shiva is shown  in both compassionate and terrifying ways. In beneficent versions, he is described as an omniscient Yogi who lives as a householder with his wife Parvati and two children, Ganesha and Kartikeya, on Mount Kailash. He is frequently seen killing demons in his ferocious forms. Adiyogi Shiva is Shiva’s other name, and he is the patron deity of yoga, meditation, and the arts.

in both compassionate and terrifying ways. In beneficent versions, he is described as an omniscient Yogi who lives as a householder with his wife Parvati and two children, Ganesha and Kartikeya, on Mount Kailash. He is frequently seen killing demons in his ferocious forms. Adiyogi Shiva is Shiva’s other name, and he is the patron deity of yoga, meditation, and the arts.

The serpent around Shiva’s neck, the adorning crescent moon, the holy river Ganga flowing from his matted hair, the third eye on his forehead (the eye that when opened turns everything in front of it into ashes), the trishula or trident as his weapon, and the damaru drum are all iconographical attributes. He is frequently worshipped in the form of lingam, which is aniconic.

Shiva’s beginnings are pre-Vedic, and the modern Shiva is a merger of numerous ancient non-Vedic and Vedic deities, notably the Rigvedic storm god Rudra, who may also have non-Vedic origins, into a single primary deity. Hindus in India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia worship Shiva, a pan-Hindu god (especially in Java and Bali).

Shiva, also known as Rudra, is worshipped as the Supreme Being in Shaivism, one of the major Hindu religions. Hindus worship Shiva the most, followed by Hanuman, Ganesha, and Rama. It includes several sub-traditions, ranging from devotional dualistic theism like Shaiva Siddhanta to yoga-oriented monistic non-theism like Kashmiri Shaivism. Both the Vedas and the Agama writings are considered fundamental theological sources.

Shaivism arose from the synthesis of pre-Vedic faiths and traditions drawn from the southern Tamil Shaiva Siddhanta traditions and philosophies, which were integrated into the non-Vedic Shiva-tradition. Starting in the final years BCE, with the Sanskritization and development of Hinduism, these pre-Vedic traditions became connected with the Vedic deity Rudra and other Vedic deities, bringing non-Vedic Shiva-traditions into the Vedic-Brahmanical fold.

In the first century CE, both devotional and monistic Shaivism gained prominent, quickly becoming the main religious tradition of many Hindu countries. Soon after, it reached in Southeast Asia, inspiring the construction of hundreds of Shaiva temples on the Indonesian islands, as well as in Cambodia and Vietnam, where it co-evolved with Buddhism.

Shiva is described as the creator, preserver, and destroyer in Shaivite theology, as well as being the same as the Atman (Self) within oneself and every living entity. It has a strong connection to Shaktism, and some Shaivas visit both Shiva and Shakti temples. It is the Hindu religion that most embraces asceticism and promotes yoga, and it, like other Hindu traditions, invites people to discover and be one with Shiva inside themselves. Shaivism’s adherents are known as “Shaivites” or “Saivas.”

Origin of Shaivism

Shaivism’s beginnings are obscure and a source of discussion among researchers, as it is a mix of pre-Vedic cults and traditions, as well as Vedic civilization.

Shaivism has its roots in India dating back to ancient times. It might be a holdover from pre-historic non-Aryan religious beliefs. Images of deities resembling Siva and phallus or Siva-linga have been discovered during excavations in the Indus valley. The religion of Siva, on the other hand, grew out of the synthesis of several deities’ personalities, notably the Vedic God Rudra.

Rudra is the God of Destruction and Storm in the Rig Veda. However, in the ‘Yayur-Veda,’ a balance is struck between his destructive and beneficent natures. Rudra gained prominence through time.

Rudra or Siva is recognised as the Supreme God in the ‘Svetasvatara Upanishada’ (Mahadeva). Despite Siva’s rising significance, the cult of Siva as the Supreme God and Saivism doctrine did not flourish until the early Christian era.

Indus Valley Civilization

Some credit the Indus Valley Civilization, which flourished between 2500 and 2000 BCE. Seals discovered in archaeological digs depict a god that resembles Shiva in appearance. The Pashupati seal, for example, was regarded by early scholars as someone sat in a meditative yoga stance surrounded by animals and bearing horns. These academics have viewed the “Pashupati” (Lord of Animals, Sanskrit paupati) seal as a prototype of Shiva. These theories are described by Gavin Flood as “speculative,” as it is unclear from the seal whether the figure has three faces, is seated in a yoga stance, or is even meant to depict a human figure.

Vedic Elements

Rudra is mentioned for the first time in the Rigveda (1500–1200 BCE) in songs 2.33, 1.43, and 1.114. A Satarudriya, an influential hymn with embedded hundred epithets for Rudra, is also included in the book, which is quoted in various mediaeval Shaiva writings as well as performed in major Hindu Shiva temples today. However, the Vedic literature exclusively presents scriptural doctrine and makes no mention of Shaivism.

The theistic underpinnings of Shaivism are wrapped in a monistic structure in the Shvetashvatara Upanishad, which was likely produced before the Bhagavad Gita around the 4th century BCE. Shiva, Rudra, Maheswara, Guru, Bhakti, Yoga, Atman, Brahman, and self-knowledge are among the major concepts and ideas of Shaivism.

Emergence of Shaivism

“The construction of Saiva traditions as we understand them began during the time from 200 BC to 100 AD,” according to Gavin Flood. Shiva was probably not initially a Brahmanical god, but he was subsequently accepted into the Brahmanical fold. The pre-Vedic Shiva rose to prominence when his cult adopted a variety of “older faiths” and their mythology, and the Epics and Puranas contain pre-Vedic myths and stories from these assimilated traditions. Shiva’s ascension was aided by his connection with a number of Vedic deities, including Purusha, Rudra, Agni, Indra, Prajapati, and Vayu. Shiva’s disciples were eventually admitted into the Brahmanical fold, and they were given permission to perform some Vedic hymns.

The phrase Shiva-bhagavata is used in section 5.2.76 of Patanjali’s Mahabhasya, which dates from the 2nd century BCE. This word refers to a devotee dressed in animal skins and wielding an ayah sulikah (iron spear, trident lance) as an image representing his deity, according to Patanjali, while demonstrating Panini’s grammatical rules. The Shvetashvatara Upanishad (late 1st mill. BCE) cites Rudra, Shiva, and Maheshwaram, although its status as a theistic or monistic Shaivism literature is debatable. The first clear evidence of Pasupata Shaivism may be found in the early years of the common period.

Puranik Shaivism

The Purana literature genre evolved in India during the Gupta Dynasty (c. 320–500 CE), and several of these Puranas have significant chapters on Shaivism – along with Vaishnavism, Shaktism, Smarta Brahmin Traditions, and other themes – indicating the significance of Shaivism at the time. The Shiva Purana and the Linga Purana are two of the most prominent Shaiva Puranas from this time period.

Post-Gupta development

Beginning with Chandragupta II (Vikramaditya) (375–413 CE), most Gupta emperors were known as Parama Bhagavatas or Bhagavata Vaishnavas and were fervent Vaishnavas. The Gupta Empire, however, fell and divided following Huna invasions, particularly those of the Alchon Huns around 500 CE, eventually crumbling totally, discrediting Vaishnavism, the faith it had been so zealously supporting. The Aulikaras, Maukharis, Maitrakas, Kalacuris, and Vardhanas, newly emerging regional rulers in central and northern India, decided to adopt Shaivism instead, giving a major push to the expansion of Shiva worship. Vaisnavism remained strong in the areas of South India and Kashmir that were not touched by the events.

The Chinese Buddhist missionary Xuanzang (Huen Tsang) visited India in the early 7th century and wrote a Chinese memoir about the presence of Shiva temples throughout the North Indian subcontinent, notably in the Hindu Kush area of Nuristan. Major Shaiva temples were constructed in the central, southern, and eastern regions of the subcontinent between the 5th and 11th centuries CE, including those at Badami cave temples, Aihole, Elephanta Caves, Ellora Caves (Kailasha, cave 16), Khajuraho, Bhuvaneshwara, Chidambaram, Madurai, and Conjeevaram.

South India

Before the Vaishnava Alvars started the Bhakti movement in the 7th century, Shaivism was the dominant school in South India, coexisting with Buddhism and Jainism, and renowned Vedanta academics like Ramanuja built a philosophical and organisational framework that enabled Vaishnava flourish. Though both Hinduisms have ancient origins, Shaivism flourished in South India far earlier, as evidenced by its presence in epics such as the Mahabharata.

According to Alexis Sanderson, Shaivism’s Mantramarga served as a model for Vaishnava’s subsequent, autonomous, and very significant Pancaratrika treatises. Hindu writings such as the Isvarasamhita, Padmasamhita, and Paramesvarasamhita attest to this.

The Shaiva tradition in South India, along with the Himalayan area ranging from Kashmir to Nepal, has been one of the most important sources of preserved Shaivism-related texts from ancient and mediaeval India. In the early first century CE, the area was also a source of Hindu arts, temple construction, and merchants who helped disseminate Shaivism across Southeast Asia.

Southeast Asia

Shaivism spread from south India through Southeast Asia, and to a lesser extent from the Himalayan area to China and Tibet. In many situations, it co-evolved with Buddhism in this region. A few caves in the Thousand Buddhas Caves, for example, incorporate Shaivism principles. The evidence from epigraphy and cave art suggests that Shaiva Mahesvara and Mahayana Buddhism arrived in Indo-China around the Funan era, about in the first millennium CE. Shiva was the supreme god in Indonesia, according to temples found at archaeological sites and numerous inscriptions dating from the early era (400 to 700 CE).

Beliefs and Practices

Shaivism is centred on Shiva, however there are several sub-traditions with different theological views and rituals. They span the spectrum from dualistic devotional theism to monistic contemplative self-discovery of Shiva. There are two sub-groups within each of these theologies. Vedic-Puranics, for example, employ names like “Shiva, Mahadeva, Maheshvara, and others” interchangeably, and they utilise iconography like the Linga, Nandi, Trishula (trident), and anthropomorphic Shiva sculptures in temples to assist concentrate their rituals. Another sub-group is esoteric, which combines it with abstract Sivata (feminine energy) or Sivatva (neuter abstraction), in which the goddess (Shakti) and the deity (Shiva) are integrated with Tantra rituals and Agama teachings. Between these Shaivas and the Shakta Hindus, there is a lot of overlap.

Vedic, Puranik, and esoteric Shaivism

Alexis Sanderson, for example, divides Shaivism into three categories: Vedic, Puranik, and non-Puranik (esoteric, tantric). They group Vedic and Puranik together because of their great overlap, but distinguish Non-Puranik esoteric sub-traditions.

- Non-Puranik. These are esoteric, minority sub-traditions in which followers are initiated (diksa) into the worship of their choosing. Their objectives range from current-life emancipation (mukti) to pursuing pleasure in higher worlds (bhukti). Their

methods differ as well, ranging from meditation atimarga or “outside higher road” to recitation-driven mantras. Pashupatas and Lakula are atimarga sub-traditions. According to Sanderson, the Pashupatas had the oldest history, dating back to the 2nd century CE, as indicated by ancient Hindu literature like the Mahabharata epic’s Shanti Parva book. Tantric sub-traditions in this category may be traced back to the post-8th to post-11th centuries, depending on the location of the Indian subcontinent, and mirror the growth of Buddhist and Jain tantric traditions during this time. The dualistic Shaiva Siddhanta and Bhairava Shaivas (non-Saiddhantika) are among them, depending on whether they regard Vedic orthopraxy. These sects value secrecy, specific symbolic formulas, teacher initiation, and the search of siddhi (special powers). Theistic notions, sophisticated geometric yantra with inherent spiritual meaning, chants, and rituals are all part of several of these traditions.

methods differ as well, ranging from meditation atimarga or “outside higher road” to recitation-driven mantras. Pashupatas and Lakula are atimarga sub-traditions. According to Sanderson, the Pashupatas had the oldest history, dating back to the 2nd century CE, as indicated by ancient Hindu literature like the Mahabharata epic’s Shanti Parva book. Tantric sub-traditions in this category may be traced back to the post-8th to post-11th centuries, depending on the location of the Indian subcontinent, and mirror the growth of Buddhist and Jain tantric traditions during this time. The dualistic Shaiva Siddhanta and Bhairava Shaivas (non-Saiddhantika) are among them, depending on whether they regard Vedic orthopraxy. These sects value secrecy, specific symbolic formulas, teacher initiation, and the search of siddhi (special powers). Theistic notions, sophisticated geometric yantra with inherent spiritual meaning, chants, and rituals are all part of several of these traditions. - Vedic-Puranik. Shaivism’s majority adheres to Vedic-Puranik traditions. They venerate the Vedas and Puranas, and their views range from dualistic theism in the form of Shiva Bhakti (devotionalism) to monistic non-theism devoted to yoga and contemplative living, occasionally leaving householder life in favour of monastic spiritual pursuits. Yoga is especially prominent in nondualistic Shaivism, with the practise honed into a system known as the four-fold upaya: being pathless (anupaya, iccha-less, desire-less), divine (sambhavopaya, jnana, knowledge-full), energetic (saktopaya, kriya, action-full), and individual (anavopaya).

History & Mention in Vedas

Shaivism has been nourished by numerous texts ranging from scriptures to theological treatises throughout its history. The Vedas and Upanishads, the Agamas, and the Bhasya are among them. Shaiva academics created a complex theology, according to Gavin Flood, an Oxford University professor who specialises in Shaivism and phenomenology. The 8th century Sadyajoti, the 10th century Ramakantha, and the 11th century Bhojadeva were among the noteworthy and significant comments by dvaita (dualistic) theistic Shaivism thinkers. Numerous advaita (nondualistic, monistic) Shaivism scholars, including the 8th/9th century Vasugupta, the 10th century Abhinavagupta, and the 11th century Kshemaraja, particularly the scholars of the Pratyabhijna, Spanda, and Kashmiri Shaivism schools of theologians, challenged the dualistic theology.

Shaivism’s origins may be traced back to prehistoric India. Ancient archaeological sites like as Harappa and Mohenjo Daro have shown evidence of Shiva worship. Rudra is the name given to him in the Rig Veda. The earliest Shiva legend has him destroying Daksha’s sacrifice arena when Shiva’s wife (Sati) freely gave up her life after being humiliated by her father, Daksha.

In his work Indika, Megasthanese mentions Shiva devotion. He believed that the god worshipped by Indians was Dionysus, a Greek divinity who shared some similarities with Shiva. Images of Shiva were undoubtedly used for religious worship, according to Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. There are allusions to Shiva Bhagats, an old Saiva cult, in Panini’s Ashtadhyayi. According to Haribhadra, Lord Shiva was followed by Gautama, the author of the Nyaya sutras, and Kanada, the founder of the Vaisheshika school of philosophy, which established atomic theory.

Lakulisa, a renowned Shiva devotee, lived sometime before or during the Christian period. Under the name Pasupatha, he was instrumental in the resurgence of Saivism (the way of the animal). There is little information about his life and career. He was most likely a member of the Kalamukha sect before founding Pasupatha Saivism. For their opposing viewpoints, he attacked Jainism, Buddhism, and the Ajivaka sect. Lakulisa, who was believed by his followers to be a manifestation of Shiva himself, resurrected Hathayoga and Tantrism, as well as the practise of human and animal sacrifices. The rebirth of Saivism that began during his reign was carried on by the Bharashivas and Vakatakas.

Vedas and Principal Upanishads

The Vedas and Upanishads are universal Hindu scriptures, but the Agamas are sacred books of distinct Hindu sub-traditions. The extant Vedic literature dates from the first millennium BCE and earlier, whereas the surviving Agamas are from the first millennium CE. In Shaivism, Vedic literature is fundamental and broad, whereas Agamas are particular treatises. According to Mariasusai Dhavamony, no Agama that contradicts Vedic literature would be accepted by Shaivas in terms of philosophy and spiritual principles. “A crucial characteristic of the Tamil Saiva Siddhanta, one would almost say its defining feature,” according to David Smith, “is the assertion that its root rests in the Vedas as well as the Agamas, in what it calls the Vedagamas.” The viewpoint of this school can be summarised as follows:

The Veda is the cow, the true Agama its milk.

— Umapati, Translated by David Smith

Shaivism in Vedic times

Some ancient Saivism cults were popular in the Indian subcontinent throughout the pre-vedic period. We have evidence that Shiva or one of his aspects was worshipped by ancient people in far-flung locations such as the Mediterranean, Africa, Central Asia, and Europe. According to others, Shiva’s name comes from the Dravidian term Chivan or Shivan, which means “red colour.” Lord Shiva’s second name, Sambhu, is thought to be of Dravidian origin, and is derived from the term Chembu, or Chempu, or Sembu, which means copper or red metal. According to some, Shiva’s phallic emblem, as well as the word linga, is of Austric origin.

When we study old Celtic gods like Norse Odin and Celtic Cernunnos, we can’t help but see certain parallels to Shiva. Some historians see links between Saivism’s Tantric activities and the Mexican, American Indian, Inuit, and Australian Aboriginal peoples’ magical-religious traditions of Shamanism. It’s probable that the parallels are attributable to the fact that ancient societies’ religious beliefs arose primarily from prehistoric fertility rites and father deity and mother god customs.

Despite the fact that Saivism is the oldest of all Saivism schools and contributed significantly to the formation of the body of Hindu rituals that are today observed in most Hindu temples, it is not as popular as Vaishnavism. According to some estimations, Vaishnavism and worship of Vishnu or his different incarnations and attributes are practised by over two-thirds of Hindus. Many Hindus do, in fact, worship a variety of gods and goddesses. They will have confidence in one family deity (kula devata) or favourite god, even though they worship multiple deities (ishta devata). Numerous people worship Vishnu or one of his many avatars.

Lord Vishnu is the most popular of the Hindu gods, presumably due to his function as the preserver and rescuer, his affiliation with the goddess of prosperity, and his identification with multiple prominent incarnations who are in many ways more popular than he himself. The popularity of the Vishnu Puranas, the Bhagavadgita, and the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata also help to maintain his popularity among the populace. The Ramayana and the Bhagavadgita are present in practically every Hindu household, and few Hindus are unfamiliar with them.

People, on the other hand, could prefer Vishnu over Shiva if they had to pick between the two. Many people are put off by his description as a destroyer, his fierce forms, his identification with the quality of tamas, his formal association with graveyards, death, and destruction, and his role in the practise of intense tantric rituals and yogic practises, as well as the rigours of discipline expected of followers of various Saivism schools. People nowadays adore Shiva in his most benevolent manifestations. They go to his temples and pray for him. They perform bhajans and songs that laud his merits and characteristics. However, few people are aware with the many Saivism schools or the philosophical facts and notions.

methods differ as well, ranging from meditation atimarga or “outside higher road” to recitation-driven mantras. Pashupatas and Lakula are atimarga sub-traditions. According to Sanderson, the Pashupatas had the oldest history, dating back to the 2nd century CE, as indicated by ancient Hindu literature like the Mahabharata epic’s Shanti Parva book. Tantric sub-traditions in this category may be traced back to the post-8th to post-11th centuries, depending on the location of the Indian subcontinent, and mirror the growth of Buddhist and Jain tantric traditions during this time. The dualistic Shaiva Siddhanta and Bhairava Shaivas (non-Saiddhantika) are among them, depending on whether they regard Vedic orthopraxy. These sects value secrecy, specific symbolic formulas, teacher initiation, and the search of siddhi (special powers). Theistic notions, sophisticated geometric yantra with inherent spiritual meaning, chants, and rituals are all part of several of these traditions.

methods differ as well, ranging from meditation atimarga or “outside higher road” to recitation-driven mantras. Pashupatas and Lakula are atimarga sub-traditions. According to Sanderson, the Pashupatas had the oldest history, dating back to the 2nd century CE, as indicated by ancient Hindu literature like the Mahabharata epic’s Shanti Parva book. Tantric sub-traditions in this category may be traced back to the post-8th to post-11th centuries, depending on the location of the Indian subcontinent, and mirror the growth of Buddhist and Jain tantric traditions during this time. The dualistic Shaiva Siddhanta and Bhairava Shaivas (non-Saiddhantika) are among them, depending on whether they regard Vedic orthopraxy. These sects value secrecy, specific symbolic formulas, teacher initiation, and the search of siddhi (special powers). Theistic notions, sophisticated geometric yantra with inherent spiritual meaning, chants, and rituals are all part of several of these traditions.