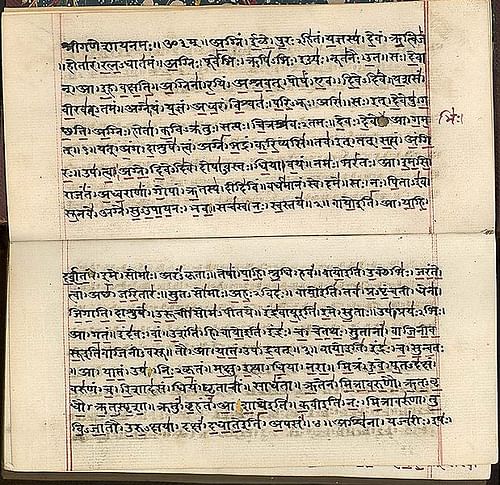

Pariśiṣṭa

A Pariśiṣṭa is a Sanskrit supplementary text appended to another fixed, more ancient text – typically Vedic literature – intended to “communicate what remains to be said”. These are in the style of sutras, but less concise. According to Max Mueller, an adherent of the Vedas, “they may be regarded as the very last fringes of Vedic literature, but they are Vedic in character and it would be difficult to account for their origin at any time except in the closing moments of the Vedas.” age.”

18 parisishtas are mentioned in early Sanskrit texts, but many more survive into the modern era, probably composed later. Parisista exists for each of the four Vedas. However, only the literature associated with the Atharvaveda is extensive, and 74 parisishtas are known, some in the form of dialogues. Vedic Parisians generally present rituals, ceremonies, the nature of hymns, and the opinions of other scholars on certain aspects of the primary text. In addition, the Atharvaveda parisishtas contain omens and parts of them survive in a very damaged form that is difficult to elucidate or interpret.

Rigveda

The Āśvalāyana Gṛhya Pariśiṣṭa is a very late text associated with the Rigveda canon. It is a short text of three chapters expanding on household rites such as daily sandhyopāsana and rites of passage such as marriage and śrāddha.

Bahvricha parisishta and Sankayana parisishta are also attached to Rigveda.

Samaveda

The Gobhila Gṛhya Pariśiṣṭa, attributed to Gobhilaputra, is a brief metrical text of two chapters of 113 and 95 verses. Its topics are covered in a manner clear to those who understand Vedic Sanskrit. The first chapter deals with the physical aspects of sacred cosmic rituals, such as the names of the 37 types of sacred fires, the rules and measures for firewood, the preparation of the sacred site, and the timing of each cosmic activity. The second chapter deals mainly with the main domestic ceremonies such as marriage or Shrāddha (communication with ancestral beings). Notable are commands such as that a girl should be given in marriage before she reaches puberty.

A second short text, the Chāndogya Pariśiṣṭa, has roughly similar coverage.

Yajurveda

The Kātiya Pariśiṣṭas, attributed to Kātyāyana, consist of 18 works listed separately in the fifth series (Caraṇavyūha): Six other works of a Parisian character are also traditionally attributed to Kātyāyana, including a work of the same name) but (Pratijña different contents. It is doubtful how many of these 24 are actually attributed to Kātyāyana; in all probability they were composed by different authors at different times, the Pratijña and Caraṇavyūha being among the latest, as they mention others.

Kṛṣṇa (Black)

The Kṛṣṇa Yajurveda has 3 parisistas:

- The Āpastamba Hautra Pariśiṣṭa, which is also found as the second praśna of the Satyasāḍha Śrauta Sūtra, specifies the duties of the Hotṛ priest in haviryajñas other than the darśapūrṇmāsa (New and Full Moon sacrifice).

- The Vārāha Śrauta Sūtra Pariśiṣṭa.

- The Kātyāyana Śrauta Sūtra Pariśiṣṭa.

Atharvaveda

For the Atharvaveda, there are 79 works, collected as 72 distinctly named parisistas.

Any little thing overlooked by the authors of the sutras is marked as a matter of grave importance. Subjects on which general instructions were formerly considered sufficient are now dealt with in special treatises, intended for men who would no longer need to trouble themselves by reading the whole system of Brahmanical ceremonial. The technical and austere language of the Sutras was exchanged for a free and easy style, whether in prose or meter; and however close in time the Brahmins may place the authors of the Sutras and some of the Parisishtas, it is certain that no man who had mastered the style of the Sutras would ever have been promoted to use the languid diction of the Parisishtas.

The change in the position and characters of the Brahmins, as found in the Sutras and as found again in the Parisishtas, was rapid and decisive. Men who could write such works were aware of their own weakness and probably suffered many defeats. The world around them was moving in a new direction, and the old Vedic age had vanished in a helpless twitch. Considerations like these tend to fix the Sutra period, as a phase in the literary history of India, as about contemporary with the first rise of Buddhism; and led the Parisishtas to recognize the representatives of a later age which witnessed the triumphs of Buddhism and the temporary decline of Brahmanical learning and power.

The real political triumph of Buddhism dates from Asoka and his council, about the middle of the third century BCE, and while most of the Yedic sutras belong to this and previous centuries, none of the Parisishta was probably written before that.